A atitude pessoal

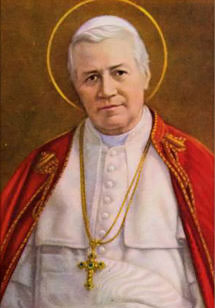

Na festa de São Pio X, pedimos a intercessão de tão insígne Pontífice para que imitemos o seu exemplo de caridade e zelo.

Desde sua primeira encíclica, Pio X urgia por caridade mesmo para com “aqueles que se nos opõe e persegue, vistos, talvez, como piores do que realmente são”. Esta caridade não era um sinal de fraqueza, mas estava fundamentada na esperança: “a esperança”, escreveu o Papa, “de que a chama da caridade Cristã, paciente e afável, dissipará as trevas de suas almas e trará a luz e a paz de Deus”.

Pio X também tinha sua esperança – de ver os adversários da Igreja emendando seus caminhos e renunciando seus erros – no que diz respeito aos modernistas.

Os testemunhos que citaremos o provarão de maneira incontestável. Mas Pio X fez mais: discretamente deu assistência financeira a alguns deles ou lhes arranjou outros ofícios; em outros casos, mostrou-se prudente antes de condená-los. Era esta generosidade, nada excepcional, incompatível com sua determinação na luta contra o modernismo? Como pode o mesmo homem que impõe sanções, depõe clérigos, excomunga, simultaneamente mostrar-se caridoso e contido? Durante o processo de beatificação, o Promotor da Fé apresentou uma série de objeções; uma delas era: “Sejamos francos: a questão, a única questão que, a meu ver, parece se levantar neste grande inquérito, é saber se Pio X, em sua luta contra o modernismo, ultrapassou as fronteiras da prudência e da justiça, particularmente em seus últimos anos…” [Novae Animadversiones, citado em Conduite de s. Pie X, p. 14] A isso, o Postulador da Causa respondeu com um volumoso dossiê de mais de 300 páginas no qual mostrava que Pio X era “firme em seus princípios, correto em suas intenções e paciente e afável com aqueles com quem lidava, mesmo se tivesse razões justas para expressar sua angústia por causa deles”. [Ibid., p. 20]

Voltamo-nos a esta questão da atitude pessoal de Pio X para com os modernistas e citaremos vários casos. Os contemporâneos de Pio X talvez desconhecessem esses gestos de caridade e justiça da parte do Pontífice. No dia seguinte à morte do Papa, Mons. Mignot, que era próximo dos modernistas, repreendeu o falecido nos seguintes termos: “Pio X era um santo, com um desinteresse raro para um italiano, mas suas idéias absolutas paralisavam seu coração… Ele esmagou muitas almas, a quem um pouco de ternura teria mantido no caminho correto”. [Carta de Mons. Mignot a Hügel, 9 de setembro de 1914, citado por Poulat, Histoire, dogma et critique, p. 480] Os historiadores do modernismo não mencionam os gestos de caridade ou justiça de Pio X, ou o fazem apenas de passagem. O número e a consistência destes atos mostram, todavia, que não foram resultados de decisões excepcionais de sua parte, mas manifestavam uma disposição intelectual e uma atitude espiritual. Na luta contra o fenômeno do modernismo, todos os métodos eram usados, e sem piedade, pois Pio X considerava que a fé dos fiéis estava em perigo e que o futuro da Igreja estava em jogo; por outro lado, quando se tratava da sorte dos modernistas, Pio X, sabendo-o, fazia grande esforço para ser o mais justo, prudente e caridoso possível.

Um exame das relações de Pio X com Loisy, o mais famoso dos modernistas, dá-nos uma boa idéia de seus profundos sentimentos. Como já vimos, quando Loisy manifestou sua disposição de se submeter, Pio X exigia, insistia que o exegeta francês devesse fazer uma completa e sincera submissão “com seu coração”. Loisy, que persistiu em seus erros após a Pascendi, acabou excomungado. Viveu em retiro em Ceffonds, Haute-Marne, e logo seria eleito para o Collège de France. No entanto, Pio X não o via como um filho perdido da Igreja. Em 1908, recebendo o novo bispo de Châlons, Dom Sevin, Pio X recomendou-lhe Loisy (a quem ele havia excomungado há pouco tempo). As palavras do Papa foram relatadas pelo próprio Loisy: “O senhor será o bispo do Pe. Loisy. Se tiver a oportunidade, trate-o com gentileza; e se ele der um passo em sua direção, dê dois na direção dele”. [Loisy, Mémoires, vol. III, p. 27. Pe. Lagrange dá outra versão destas palavras, versão que ouviu da boca de Dom Sevin; quando o bispo de Châlons perguntara ao Papa que atitude deveria adotar com relação a Loisy se este demonstrasse arrependimento, o Papa respondeu: Recebei-o de braços abertos. Digo ao senhor que ele, meu filho, irá voltar” (Lagrange, M. Loisy et le modernisme, p. 138)]

Outro caso é o do Pe. Murri. Como veremos, a Liga Nacional Democrática que fundara foi condenada pelo Papa. Ele tinha conhecidos laços com modernistas. Em abril de 1907, no despertar de uma série de artigos nos quais Murri amargamente criticava a política do Vaticano na França, Pio X enviou uma carta ao bispo da diocese deste líder democrático, instruindo-o a informar a este último que estava suspenso a divinis. Quando, alguns meses depois, a Encíclica Pascendi estava prestes a ser publicada, havia uma certa expectativa de que Murri fosse imediatamente excomungado, dado que estava absolutamente claro que o turbulento líder democrata cristão se oporia à Encíclica. O problema foi colocado a Pio X, que preferiu ser paciente. Em 25 de agosto de 1907, escreveu à Congregação do Santo Ofício: “Se tudo estiver em ordem com o celebret do Pe. Romolo Murri, ele não pode, sem grave injustiça, ser proibido de rezar Missa, na medida em que não realizou qualquer ato condenado pela Encíclica”. [Citado por Dal-Gal, Pie X, p. 404] Murri, contudo, persistiu publicamente em suas posições e foi, ao fim, excomungado em 1909. Posteriormente, ele experimentou graves dificuldades financeiras; Pio X soube disso e pagou-lhe uma pensão mensal.[Depoimento do Cardeal Merry del Val, Summarium, p. 195]

[…]

Pio X tinha de levar muitas coisas em consideração: a salvaguarda da fé e do bem da Igreja, a necessidade e a legitimidade de estudos em matérias de religião, o bem pessoal e a boa fé das pessoas envolvidas, assim como as manobras, as ambições e o zelo das partes. Enquanto Papa, seu dever eram aqueles primeiros; como cristão, estava obrigado a seguir a caridade, prudência e justiça. [...] Pio X sentia como seu dever, enquanto guardião da fé, combater o modernismo, e fazê-lo usando os mais variados métodos e sem fraqueza, pois, como via, a própria existência da Igreja estava ameaçada. Ao mesmo tempo, sem fazer qualquer concessão ao erro, esforçava-se por ajudar os culpados ou suspeitos, e tomava grande cuidado em limitar os excessos dos anti-modernistas. Uma de suas máximas favoritas era: “devemos combater o erro sem ferir as pessoas envolvidas”.

Saint Pius X, Restorer of the Church – Yves Chiron, Angelus Press, 2002, pp. 236-237;241-242. Tradução: Fratres in Unum.com.

Festividad de San Pio X, Papa y Confesor, y 102º Aniversario del Juramento Anti-modernista

Hoy se celebra la festividad de San Pío PP. X, dos días después del centésimo primer aniversario de su Motu Proprio "Sacrorum Antistitum" contra el Modernismo. En dicho motu proprio se imponía a todo el clero el JURAMENTO CONTRA LOS ERRORES DEL MODERNISMO, que fue obligatorio desde septiembre de 1910 hasta julio de 1967, pero cuyo contenido sigue siendo Doctrina de la Iglesia.

Bajo estas líneas pongo íntegro el texto del juramento en español:

FÓRMULA DEL JURAMENTO

Yo, _________ , abrazo y acepto firmemente todas y cada una de las cosas que han sido definidas, afirmadas y declaradas por el Magisterio inerrante de la Iglesia, principalmente aquellos puntos de doctrina que directamente se oponen a los errores de la época presente.

Y en primer lugar: profeso que Dios, principio y fin de todas las cosas, puede ser ciertamente conocido y, por tanto, también demostrado, como la causa por sus efectos, por la luz natural de la razón mediante las cosas que han sido hechas, es decir, por las obras visibles de la creación.

En segundo lugar: admito y reconozco como signos certísimos del origen divino de la religión cristiana los argumentos externos de la revelación, esto es, hechos divinos, y en primer término, los milagros y las profecías, y sostengo que son sobremanera acomodados a la inteligencia de todas las épocas y de los hombres, aun los de este tiempo.

En tercer lugar: creo igualmente con fe firme que la Iglesia, guardiana y maestra de la palabra revelada, fue próxima y directamente instituida por el mismo verdadero e histórico Cristo, mientras vivía entre nosotros, y que fue edificada sobre Pedro, príncipe de la jerarquía apostólica, y sus sucesores para siempre.

Cuarto: acepto sinceramente la doctrina de la fe transmitida hasta nosotros desde los Apóstoles por medio de los Padres ortodoxos siempre en el mismo sentido y en la misma sentencia; y por tanto, de todo punto rechazo la invención herética de la evolución de los dogmas, que pasarían de un sentido a otro diverso del que primero mantuvo la Iglesia; igualmente condeno todo error, por el que al depósito divino, entregado a la Esposa de Cristo y que por ella ha de ser fielmente custodiado, sustituye un invento filosófico o una creación de la conciencia humana, lentamente formada por el esfuerzo de los hombres y que en adelante ha de perfeccionarse por progreso indefinido.

Quinto: Sostengo con toda certeza y sinceramente profeso que la fe no es un sentimiento ciego de la religión que brota de los escondrijos de la subconsciencia, bajo presión del corazón y la inclinación de la voluntad formada moralmente, sino un verdadero asentimiento del entendimiento a la verdad recibida por fuera por oído, por el que creemos ser verdaderas las cosas que han sido dichas, atestiguadas y reveladas por el Dios personal, creador y Señor nuestro, y lo creemos por la autoridad de Dios, sumamente veraz.

También me someto con la debida reverencia y de todo corazón me adhiero alas condenaciones, declaraciones y prescripciones todas que se contienen en la Carta Encíclica Pascendi y en el Decreto Lamentabili, particularmente en lo relativo a la que llaman historia de los dogmas.

Asimismo repruebo el error de los que afirman que la fe propuesta por la Iglesia puede repugnar a la historia, y que los dogmas católicos en el sentido en que ahora son entendidos, no pueden conciliarse con los auténticos orígenes de la religión cristiana.

Condeno y rechazo también la sentencia de aquellos que dicen que el cristiano erudito se reviste de doble personalidad, una de creyente y otra de historiador, como si fuera lícito al historiador sostenerlo que contradice a la fe del creyente, o sentar premisas de las que se siga que los dogmas son falsos y dudosos, con tal de que éstos no se nieguen directamente.

Repruebo igualmente el método de juzgar e interpretar la Sagrada Escritura que, sin tener en cuenta la tradici6n de la Iglesia, la analogía de la fe y las normas de la Sede Apostólica, sigue los delirios de los racionalistas y abraza no menos libre que temerariamente la crítica del texto como regla única y suprema.

Rechazo además la sentencia de aquellos que sostienen que quien enseña la historia de la teología o escribe sobre esas materias, tiene que dejar antes a un lado la opinión preconcebida, ora sobre el origen sobrenatural de la tradición católica, ora sobre la promesa divina de una ayuda para la conservación perenne de cada una de las verdades reveladas, y que además los escritos de cada uno de los Padres han de interpretarse por los solos principios de la ciencia, excluida toda autoridad sagrada, y con aquella libertad de juicio con que suelen investigarse cualesquiera monumentos profanos.

De manera general, finalmente, me profeso totalmente ajeno al error por el que los modernistas sostienen que en la sagrada tradición no hay nada divino, o lo que es mucho peor, lo admiten en sentido panteístico, de suerte que ya no quede sino el hecho escueto y sencillo, que ha de ponerse al nivel de los hechos comunes de la historia, a saber: unos hombres que por su industria, ingenio y diligencia, continúan en las edades siguientes la escuela comenzada por Cristo y sus Apóstoles.

Por tanto, mantengo firmísimamente la fe de los Padres y la mantendré hasta el postrer aliento de mi vida sobre el carisma cierto de la verdad, que está, estuvo y estará siempre en la sucesión del episcopado desde los Apóstoles; no para que se mantenga lo que mejor y más apto pueda parecer conforme a la cultura de cada época, sino para que nunca se crea de otro modo, nunca de otro modo se entienda la verdad absoluta e inmutable predicada desde el principio por los Apóstoles.

Todo esto prometo que lo he de guardar íntegra y sinceramente y custodiar inviolablemente sin apartarme nunca de ello, ni enseñando ni de otro modo cualquiera de palabra o por escrito.

Así lo prometo, así lo juro, así me ayude Dios y estos Santos Evangelios de Dios.

HOJE É A FESTA DE S. PI

St. Pius X – September 3

St. Pius X – September 3

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

The life of St. Pius X speaks to us in so many ways that it is difficult to choose the one with a more formative character. But we can begin by stressing a curious facet of his life that also signifies an aspect of the life of the Church.

The times of Pius IX and Leo XIII

We know that Pius IX, the predecessor of St. Pius X, was a prototype of a counter-revolutionary Pope. He proclaimed the dogmas of Papal Infallibility and the Immaculate Conception; he fought on every front of combat and was attacked on all of them by the Revolution. His pontificate closed at the apex of his confrontation with the Revolution, with the troops of Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel taking Rome as well as the Pontifical Territories from the Pope.

Giuseppe Melchiorre Sarto, St. Pius X

After Pius IX, whose process of canonization is ongoing, came Leo XIII. I have never heard anyone propose a process of canonization for him. There is no record that even his greatest enthusiasts ever considered this possibility. Recently (these comments were made in 1966), an ensemble of letters by Leo XIII to his family was published by a German scholar, who, with that delightful naiveté of many Germans, presented them exactly as they were written. I believe that those letters destroyed any possibility of the canonization of Leo XIII.

From a small perspective – because those letters reflect only a very small part of his life – Leo XIII revealed in them his great concern about the glory of the Pecci family, that is, his own family. He had been Count Pecci. So, there are letters to his sister, his mother, and other members of the family remarking how he did this and that as Pope, and that his actions would bring great glory for the Pecci family. The lackluster name of the Pecci family, he noted, would now be immortal! The publication of these candid letters found an icy reception from the Italian press, and given its inconvenience, the book was more or less set aside and forgotten.

To show how such an attitude is unbefitting the role of a Pope, let me remind you of an episode that took place in the Middle Ages. Pope Innocent III was reigning. His pontificate was praiseworthy in many aspects. But he had the weakness to construct a tower in honor of his family, the Conti family. He built the Torre dei Conti over a site where Roman Emperors used to erect historical monuments for their personal glory. Perhaps Innocent III was trying to compare himself to them. The tower is still there, near the Coliseum.

Innocent III commanded that the Tower of the Conti, above, be built to glorify his own family

A holy religious woman, whose name I don’t recall at this moment, had a vision that she communicated to the Pope about this tower. In the revelation Our Lord ordered her to tell Innocent III that because he made that tower to glorify his family, he would remain in Purgatory until the last day of the world. Here is a criterion to understand what Leo XIII’s vainglory regarding his family probably represented in the eyes of God.

Leo XIII was a Pope whose pontificate could be symbolized by the ralliement [in French, re-uniting], the policy of uniting Catholic social-political views with the Masonic ideals of the French Revolution, until then strongly condemned by the Church. That is, a policy diametrically opposed to that of Pius IX.

St. Pius X was the counter-revolutionary Pope who condemned the Sillon, condemned Modernism, and re-established the Catholic position in France that had been shaken by the ralliement. He was also the one who instituted the policy of permitting First Communion for children at the age of reason, among many other splendid things he did.

Leo XIII had a very long pontificate, so long that he saw the deaths of all the Cardinals who had elected him. When the last of these Cardinals died, he had a medal stamped saying to the body of Cardinals he had created: “It was not you who chose me, but I who chose you.” It was another manifestation of vainglory. It was this body of Cardinals created by Leo XIII that, after he died, elected Pope St. Pius X.

A mysterious inner force that restores the Church

The fact of his election illustrates something of a mystery that exists in the life of the Church. Given her intrinsic sanctity, everything follows in accord with the plans of God when the hour of Divine Providence arrives. At the hour when God wants to intervene, even in the darkest, more incomprehensible, and almost hopeless situation, a force acts in the Church and it moves the action of men and the reaction of the Catholic grassroots in the most unexpected and inconceivable ways.

The surprise election of Giuseppe Sarto announced in the Observatorre Romano the next day

The election of St. Pius X was like this, and it shows us that we should always consider the possibility that this institutional force will intervene and do something that we could not imagine. This force comes from the presence of Our Lord in the Church. More than in any other domain of creation, in the Church a word from Him has a decisive weight and can change everything. When things go awry in the Church, it is because God chooses not to intervene. Our Lord sleeps in the bark of the Church, like He slept in the boat with the Apostles. Our Lord was sleeping as the storm reached its apex. The Apostles became fearful and awakened Him. Then He ordered the storm to stop, and there was a great calm. How many times in the History of the Church has Our Lord seemed to be sleeping! Perhaps if we would pray more for Him to awaken, things would be different.

With the election of St. Pius X, this happened. Cardinal Sarto made no effort to be elected. On the contrary, he made a resistance to his own election, perhaps because he perceived the overwhelming weight that he would have to carry on his shoulders. Finally he accepted, but he lacked some of the many capacities necessary to exercise the pontifical function. He was not an accomplished diplomat, for example, and was unfamiliar with the great political questions of the time. He needed someone to help him govern with regard to these important matters.

Then he became acquainted with Cardinal Merry del Val. When St. Pius X accepted the Papacy, he had no idea how he would be able to deal with those questions, but God put the necessary man near him. This is just one highlight of his glorious pontificate.

Fulmination of Modernism

When St. Pius X rose to the Pontifical Throne, a large part of the good Catholic press was so discouraged and defeated that it was near death. Almost all the elements of the Counter-Revolution were in an analogous state. I read a report of a Catholic French ultramontane of that time in which he described how his movement was so devastated that they did not even realize during the first years of St. Pius X’s pontificate that he was their champion. The nightmare they had endured under Leo XIII had lasted so long that it took some time for them to awaken from that dark night, and begin to marvel at the true dawn St. Pius X represented for the good cause.

It is good for us to consider what his condemnation of Modernism represented. A conspiracy had been established inside the Church, like a conspiracy inside a country, in order to usurp the supreme power. It intended to submit the Church to a series of reforms in order to adapt her to the errors of the Revolution. It wanted to establish democracy throughout the Church; it wanted the Church to support and collaborate with all the political leftist parties and movements; it prepared a false ecumenism to be made with all false religions in order to spread religious indifferentism everywhere so that no one would have certainty about the one true Faith. For Modernism the faith inside of each person was sufficient. In brief, it wanted the Catholic Church to stop being herself.

St. Pius X discovered this conspiracy, and fulminated against it with his documents. This is the first great characteristic of his pontificate, which would be enough to immortalize him. Imagine if he had failed to do so. Today, any reaction against Communism and Progressivism would be impossible. We are still in this fight because he smashed Modernism at the beginning of the 20th century. We are here now, because of the fierce energy of St. Pius X.

He inherited from his predecessor a notable work, the restoration of Scholasticism. However, as soon as Leo XIII died, Scholasticism began to be distorted in order to accommodate Modernism. St. Pius X elaborated a summary of the fundamental thesis of Thomism – a kind of appendix to the Encyclical Aeterni Patris – which he obliged all teachers and professors of theology and philosophy to accept under oath. With this he preserved the great edifice of Scholasticism from corruption.

Against the ideals of the French Revolution

At that time, France was the most influential nation in the world. The political and social life of France, the pro and con positions of anti-clericalism, the confrontation between Revolution and Counter-Revolution were followed and imitated by almost the whole world. Years before, the Prince of Metternich, a famous Austrian minister, expressed this well in a very picturesque way, saying, “When France has a cold, all Europe sneezes.” This influence continued into the time of St. Pius X.

The beatification of St. Joan of Arc recalled the Catholic support for the monarchy in France

In the France of those days, there was a strong tendency, even among the Bishops, to accept the separation between the Church and the State, along with other principles of the French Revolution. St. Pius X prepared a bomb to destroy this position. It was his Encyclical Vehementer Nos, in which he laid to rest all the hopes of Laicism in France, the compromises being proposed by the French government and the Liberal clergy, and initiated a true ideological war against the revolutionary French regime. This bomb stopped or slowed down the march of Revolution in its ensemble for a long time in France.

He gave another important blow against the ideals of the French Revolution when he announced the the beatification of St. Joan of Arc, an action that strongly displeased the Revolution, because St. Joan of Arc represented Catholic France holding a sword for the restoration of the legitimate monarchy. She also fought to maintain the integrity of the French borders. The announcement of her beatification caused a tremendous joy among the French people, and it considerably strengthened the Catholic ultramontane cause.

The importance of early Communion for children

Another great thing that St. Pius X did was to allow Communion for children at age 7 and encourage daily Communion. I sustain that this measure, besides having all the spiritual advantages we know, created an enormous difficulty for the Devil and his cohorts to have power over many souls.

Permitting early First Communion for children struck a strong blow to the Revolution

Let me explain this point. Before this measure of St. Pius X, Catholics would make their First Communion only in their late childhood or adolescence, after many mortal sins would have already been committed, giving the Devil a special power over them. For this reason, many souls abandoned the Catholic Faith even before they received First Communion, making them an easy prey for the Devil and Secret Societies.

On the contrary, in a child who receives his First Communion in the state of his first innocence and has the possibility of making frequent Communions, Our Lord establishes Himself with a special power over the soul and, consequently, diminishes the power of the Devil. This also diminishes the power of Masonry and other Secret Societies over those Catholics who become members of such organizations. Their power over those members will never be as great as it would have been had they not received First Communion as children.

I consider this measure of St. Pius X as a fundamental cause for the loss of influence and dominion of Masonry over its members. I am not talking about its control over world events, where Masonry became more powerful, but rather its control over the interior of souls, where it became weaker.

A Prophet who was rejected

St. Pius X was not only a good Pope; he was a saint and a counter-revolutionary. In a certain way he was also a prophet. He made a last appeal for the people of his era to persevere and prevent the chastisements that could come. If the world would not listen to his appeal, then World War I would come as a chastisement. Cardinal Merry del Val reported in his memoirs that St. Pius X predicted the war as the end of an era. One can see that there is a link between St. Pius X and Fátima. Since his pontificate was not well accepted, the war came, and this was a principle cause for the rise of Communism in Russia, and afterward, the dissemination of its errors all over the world. One thing is linked to the other.

Pope St. Pius X

The magazine La Critique du Liberalisme [The Critique of Liberalism] published an article about the death of St Pius X. The author sustains the thesis that St. Pius X was murdered on the order of Masonry. He affirms that St. Pius X caught a simple cold, but suddenly and inexplicably that cold would cause his death. One morning when he awakened, he could no longer speak, which was not proportional to that cold; he tried to write in order to communicate something, but also found himself unable to write. Soon afterward he died.

The author also tells about a young, brilliant naval officer in Prussia who became a Jesuit. After being ordained, he became a nurse and was named to take care of the Pope during that cold. On that final night of the life of St. Pius X, he was closely attending the Pope. After the Pope died, the Jesuit returned to Prussia, left the Order, and returned to a brilliant career as a naval officer. During the war he became a submarine commander. The author affirms that St. Pius X was killed on the order of the German Masonry, and therefore, would be a martyr. I repeat the thesis of this article without having formed my own opinion on it.

In his memoirs Cardinal Merry del Val confirms that St. Pius X could not speak or write, and he adds: “No one will ever know what happened that night.” It is a mysterious phrase.

In 1950, I followed the funeral ceremonies for Marc Sangnier in the French press. Sangnier had been the leader of the Sillon movement, which was condemned by St. Pius X in the Encyclical Notre charge apostolique. The burial of Sangnier was a veritable apotheosis. His body was exposed for public viewing in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, the burial cortege was followed by members of the French government, Senate, House of Representatives, diplomatic body, and numerous ecclesiastics. All this was done in a spirit of protest against the condemnation St. Pius X made of Modernism.

One year later, St. Pius X was beatified. There were no celebrations in France, at least nothing that came close to those for Sangnier. This shows how St. Pius X was rejected.

Even with this hatred, Divine Providence made the memory of St. Pius X shine above the firmament of the Church to illuminate the dark days that would come after him. He is an astral body, like a moon, that prolongs the glimmer of the Papacy amid the darkness that fell over the Church after his death.

What should we ask of St. Pius X? There are so many things to ask that the best advice is to ask for everything: the unexpected victories, perseverance, the gift of raising the fury of the enemies, astuteness, and the courage to walk even to a martyr’s death if necessary.

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

source

The Saint of the Day features highlights from the lives of saints based on comments made by the late Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira. Following the example of St. John Bosco who used to make similar talks for the boys of his College, each evening it was Prof. Plinio’s custom to make a short commentary on the lives of the next day’s saint in a meeting for youth in order to encourage them in the practice of virtue and love for the Catholic Church.

Prof. Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira

| The life of St. Pius X speaks to us in so many ways that it is difficult to choose the one with a more formative character. But we can begin by stressing a curious facet of his life that also signifies an aspect of the life of the Church. The times of Pius IX and Leo XIII We know that Pius IX, the predecessor of St. Pius X, was a prototype of a counter-revolutionary Pope. He proclaimed the dogmas of Papal Infallibility and the Immaculate Conception; he fought on every front of combat and was attacked on all of them by the Revolution. His pontificate closed at the apex of his confrontation with the Revolution, with the troops of Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel taking Rome as well as the Pontifical Territories from the Pope.

From a small perspective – because those letters reflect only a very small part of his life – Leo XIII revealed in them his great concern about the glory of the Pecci family, that is, his own family. He had been Count Pecci. So, there are letters to his sister, his mother, and other members of the family remarking how he did this and that as Pope, and that his actions would bring great glory for the Pecci family. The lackluster name of the Pecci family, he noted, would now be immortal! The publication of these candid letters found an icy reception from the Italian press, and given its inconvenience, the book was more or less set aside and forgotten. To show how such an attitude is unbefitting the role of a Pope, let me remind you of an episode that took place in the Middle Ages. Pope Innocent III was reigning. His pontificate was praiseworthy in many aspects. But he had the weakness to construct a tower in honor of his family, the Conti family. He built the Torre dei Conti over a site where Roman Emperors used to erect historical monuments for their personal glory. Perhaps Innocent III was trying to compare himself to them. The tower is still there, near the Coliseum.

Leo XIII was a Pope whose pontificate could be symbolized by the ralliement [in French, re-uniting], the policy of uniting Catholic social-political views with the Masonic ideals of the French Revolution, until then strongly condemned by the Church. That is, a policy diametrically opposed to that of Pius IX. St. Pius X was the counter-revolutionary Pope who condemned the Sillon, condemned Modernism, and re-established the Catholic position in France that had been shaken by the ralliement. He was also the one who instituted the policy of permitting First Communion for children at the age of reason, among many other splendid things he did. Leo XIII had a very long pontificate, so long that he saw the deaths of all the Cardinals who had elected him. When the last of these Cardinals died, he had a medal stamped saying to the body of Cardinals he had created: “It was not you who chose me, but I who chose you.” It was another manifestation of vainglory. It was this body of Cardinals created by Leo XIII that, after he died, elected Pope St. Pius X. A mysterious inner force that restores the Church The fact of his election illustrates something of a mystery that exists in the life of the Church. Given her intrinsic sanctity, everything follows in accord with the plans of God when the hour of Divine Providence arrives. At the hour when God wants to intervene, even in the darkest, more incomprehensible, and almost hopeless situation, a force acts in the Church and it moves the action of men and the reaction of the Catholic grassroots in the most unexpected and inconceivable ways.

With the election of St. Pius X, this happened. Cardinal Sarto made no effort to be elected. On the contrary, he made a resistance to his own election, perhaps because he perceived the overwhelming weight that he would have to carry on his shoulders. Finally he accepted, but he lacked some of the many capacities necessary to exercise the pontifical function. He was not an accomplished diplomat, for example, and was unfamiliar with the great political questions of the time. He needed someone to help him govern with regard to these important matters. Then he became acquainted with Cardinal Merry del Val. When St. Pius X accepted the Papacy, he had no idea how he would be able to deal with those questions, but God put the necessary man near him. This is just one highlight of his glorious pontificate. Fulmination of Modernism When St. Pius X rose to the Pontifical Throne, a large part of the good Catholic press was so discouraged and defeated that it was near death. Almost all the elements of the Counter-Revolution were in an analogous state. I read a report of a Catholic French ultramontane of that time in which he described how his movement was so devastated that they did not even realize during the first years of St. Pius X’s pontificate that he was their champion. The nightmare they had endured under Leo XIII had lasted so long that it took some time for them to awaken from that dark night, and begin to marvel at the true dawn St. Pius X represented for the good cause. It is good for us to consider what his condemnation of Modernism represented. A conspiracy had been established inside the Church, like a conspiracy inside a country, in order to usurp the supreme power. It intended to submit the Church to a series of reforms in order to adapt her to the errors of the Revolution. It wanted to establish democracy throughout the Church; it wanted the Church to support and collaborate with all the political leftist parties and movements; it prepared a false ecumenism to be made with all false religions in order to spread religious indifferentism everywhere so that no one would have certainty about the one true Faith. For Modernism the faith inside of each person was sufficient. In brief, it wanted the Catholic Church to stop being herself. St. Pius X discovered this conspiracy, and fulminated against it with his documents. This is the first great characteristic of his pontificate, which would be enough to immortalize him. Imagine if he had failed to do so. Today, any reaction against Communism and Progressivism would be impossible. We are still in this fight because he smashed Modernism at the beginning of the 20th century. We are here now, because of the fierce energy of St. Pius X. He inherited from his predecessor a notable work, the restoration of Scholasticism. However, as soon as Leo XIII died, Scholasticism began to be distorted in order to accommodate Modernism. St. Pius X elaborated a summary of the fundamental thesis of Thomism – a kind of appendix to the Encyclical Aeterni Patris – which he obliged all teachers and professors of theology and philosophy to accept under oath. With this he preserved the great edifice of Scholasticism from corruption. Against the ideals of the French Revolution At that time, France was the most influential nation in the world. The political and social life of France, the pro and con positions of anti-clericalism, the confrontation between Revolution and Counter-Revolution were followed and imitated by almost the whole world. Years before, the Prince of Metternich, a famous Austrian minister, expressed this well in a very picturesque way, saying, “When France has a cold, all Europe sneezes.” This influence continued into the time of St. Pius X.

He gave another important blow against the ideals of the French Revolution when he announced the the beatification of St. Joan of Arc, an action that strongly displeased the Revolution, because St. Joan of Arc represented Catholic France holding a sword for the restoration of the legitimate monarchy. She also fought to maintain the integrity of the French borders. The announcement of her beatification caused a tremendous joy among the French people, and it considerably strengthened the Catholic ultramontane cause. The importance of early Communion for children Another great thing that St. Pius X did was to allow Communion for children at age 7 and encourage daily Communion. I sustain that this measure, besides having all the spiritual advantages we know, created an enormous difficulty for the Devil and his cohorts to have power over many souls.

On the contrary, in a child who receives his First Communion in the state of his first innocence and has the possibility of making frequent Communions, Our Lord establishes Himself with a special power over the soul and, consequently, diminishes the power of the Devil. This also diminishes the power of Masonry and other Secret Societies over those Catholics who become members of such organizations. Their power over those members will never be as great as it would have been had they not received First Communion as children. I consider this measure of St. Pius X as a fundamental cause for the loss of influence and dominion of Masonry over its members. I am not talking about its control over world events, where Masonry became more powerful, but rather its control over the interior of souls, where it became weaker. A Prophet who was rejected St. Pius X was not only a good Pope; he was a saint and a counter-revolutionary. In a certain way he was also a prophet. He made a last appeal for the people of his era to persevere and prevent the chastisements that could come. If the world would not listen to his appeal, then World War I would come as a chastisement. Cardinal Merry del Val reported in his memoirs that St. Pius X predicted the war as the end of an era. One can see that there is a link between St. Pius X and Fátima. Since his pontificate was not well accepted, the war came, and this was a principle cause for the rise of Communism in Russia, and afterward, the dissemination of its errors all over the world. One thing is linked to the other.

The author also tells about a young, brilliant naval officer in Prussia who became a Jesuit. After being ordained, he became a nurse and was named to take care of the Pope during that cold. On that final night of the life of St. Pius X, he was closely attending the Pope. After the Pope died, the Jesuit returned to Prussia, left the Order, and returned to a brilliant career as a naval officer. During the war he became a submarine commander. The author affirms that St. Pius X was killed on the order of the German Masonry, and therefore, would be a martyr. I repeat the thesis of this article without having formed my own opinion on it. In his memoirs Cardinal Merry del Val confirms that St. Pius X could not speak or write, and he adds: “No one will ever know what happened that night.” It is a mysterious phrase. In 1950, I followed the funeral ceremonies for Marc Sangnier in the French press. Sangnier had been the leader of the Sillon movement, which was condemned by St. Pius X in the Encyclical Notre charge apostolique. The burial of Sangnier was a veritable apotheosis. His body was exposed for public viewing in the Cathedral of Notre Dame, the burial cortege was followed by members of the French government, Senate, House of Representatives, diplomatic body, and numerous ecclesiastics. All this was done in a spirit of protest against the condemnation St. Pius X made of Modernism. One year later, St. Pius X was beatified. There were no celebrations in France, at least nothing that came close to those for Sangnier. This shows how St. Pius X was rejected. Even with this hatred, Divine Providence made the memory of St. Pius X shine above the firmament of the Church to illuminate the dark days that would come after him. He is an astral body, like a moon, that prolongs the glimmer of the Papacy amid the darkness that fell over the Church after his death. What should we ask of St. Pius X? There are so many things to ask that the best advice is to ask for everything: the unexpected victories, perseverance, the gift of raising the fury of the enemies, astuteness, and the courage to walk even to a martyr’s death if necessary.

|

S. Pio X nutrì il gregge con la vera dottrina

San Pio X nutrì il gregge con la vera dottrina

Oggi ricorre la festa di San Pio X e mi piace ricordarlo, come ha fatto Rorate Caeli, con la citazione dell'Allocuzione Si Diligis rivolta da Pio XII a Cardinali, Arcivescovi e Vescovi dopo la canonizzazione del grande Pontefice, il 31 Maggio 1954. Ho messo il link all'unico testo (in latino) presente sul sito della Santa Sede.

Oggi ricorre la festa di San Pio X e mi piace ricordarlo, come ha fatto Rorate Caeli, con la citazione dell'Allocuzione Si Diligis rivolta da Pio XII a Cardinali, Arcivescovi e Vescovi dopo la canonizzazione del grande Pontefice, il 31 Maggio 1954. Ho messo il link all'unico testo (in latino) presente sul sito della Santa Sede.

E così mi sono accorta di quanto la traduzione inglese impoverisca il contenuto mirabile del testo e di quanta importanza esso abbia nei copiosi riferimenti al Magistero ed al munus docendi.

Nella ricorrenza odierna riporto, come memoriale, il significativo incipit e mi riprometto, con calma, di continuare a tradurre direttamente dal testo latino anche le altre parti che hanno costituito per me una sorpresa e ci saranno di grande utilità. A meno che qualche lettore non possa ricavare dalle raccolte il testo italiano e gentilmente me lo invii; gliene sarei molto grata.

« Se ami... pasci ». Quale sia il significato del lavoro apostolico, la sua virtù esaltata, la fonte e l'origine dei suoi meriti lo insegna il comando del nostro divin Salvatore all'apostolo Pietro, col quale ha inizio la Messa in onore di uno o più Sommi Pontefici.

Gesù Cristo, sommo ed eterno Sacerdote e Pastore delle anime, per noi ha insegnato cose grandi, ha fatto cose mirabili, ha sopportato cose molto dure. Pio X, il vescovo di Roma, che è stata nostra grande gioia iscrivere nella lista dei santi, seguendo da vicino le orme del suo Divino Maestro, ha preso il comando dalle labbra di Cristo e strenuamente, lo ha svolto: pascendo amò e amando nutrì. Amava Cristo e nutrì il suo gregge : dai tesori celesti che il misericordioso Redentore ha portato sulla terra, bevve con parsimonia quel che ha distribuito largamente al gregge : il nutrimento della verità, i misteri celesti, la suprema grazia del sacrificio e sacramento eucaristico, la dolcezza della carità, la serietà nel governo, la fortezza in difesa; ha dato tutto se stesso e quelle cose che l'Autore e Datore di ogni bene aveva elargito su di lui. [...]

Oggi ricorre la festa di San Pio X e mi piace ricordarlo, come ha fatto Rorate Caeli, con la citazione dell'Allocuzione Si Diligis rivolta da Pio XII a Cardinali, Arcivescovi e Vescovi dopo la canonizzazione del grande Pontefice, il 31 Maggio 1954. Ho messo il link all'unico testo (in latino) presente sul sito della Santa Sede.

Oggi ricorre la festa di San Pio X e mi piace ricordarlo, come ha fatto Rorate Caeli, con la citazione dell'Allocuzione Si Diligis rivolta da Pio XII a Cardinali, Arcivescovi e Vescovi dopo la canonizzazione del grande Pontefice, il 31 Maggio 1954. Ho messo il link all'unico testo (in latino) presente sul sito della Santa Sede.E così mi sono accorta di quanto la traduzione inglese impoverisca il contenuto mirabile del testo e di quanta importanza esso abbia nei copiosi riferimenti al Magistero ed al munus docendi.

Nella ricorrenza odierna riporto, come memoriale, il significativo incipit e mi riprometto, con calma, di continuare a tradurre direttamente dal testo latino anche le altre parti che hanno costituito per me una sorpresa e ci saranno di grande utilità. A meno che qualche lettore non possa ricavare dalle raccolte il testo italiano e gentilmente me lo invii; gliene sarei molto grata.

« Se ami... pasci ». Quale sia il significato del lavoro apostolico, la sua virtù esaltata, la fonte e l'origine dei suoi meriti lo insegna il comando del nostro divin Salvatore all'apostolo Pietro, col quale ha inizio la Messa in onore di uno o più Sommi Pontefici.

Gesù Cristo, sommo ed eterno Sacerdote e Pastore delle anime, per noi ha insegnato cose grandi, ha fatto cose mirabili, ha sopportato cose molto dure. Pio X, il vescovo di Roma, che è stata nostra grande gioia iscrivere nella lista dei santi, seguendo da vicino le orme del suo Divino Maestro, ha preso il comando dalle labbra di Cristo e strenuamente, lo ha svolto: pascendo amò e amando nutrì. Amava Cristo e nutrì il suo gregge : dai tesori celesti che il misericordioso Redentore ha portato sulla terra, bevve con parsimonia quel che ha distribuito largamente al gregge : il nutrimento della verità, i misteri celesti, la suprema grazia del sacrificio e sacramento eucaristico, la dolcezza della carità, la serietà nel governo, la fortezza in difesa; ha dato tutto se stesso e quelle cose che l'Autore e Datore di ogni bene aveva elargito su di lui. [...]

ST. PIUS X AND THE PRIEST

The Priesthood 2-1

RECIPE FOR HOLINESS

RECIPE FOR HOLINESS

ST. PIUS X AND THE PRIEST Nihil Obstat: Joannes McCormack, Cens. Dep. die 2 Maii 1959

Imprimatur: + Joannes Kyne Epus. Miden. die 2 Maii 1959

CONTENTS: PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

HOLINESS OF LIFE

MEANS TO HOLINESS

PIETY AND PRAYER

SACRIFICE

CHARITY

ZEAL

DIGNITY AND PROPRIETY

PREACHING

SOCIAL APOSTOLATE

The Priesthood 2-1

RECIPE FOR HOLINESS

RECIPE FOR HOLINESS ST. PIUS X AND THE PRIEST Nihil Obstat: Joannes McCormack, Cens. Dep. die 2 Maii 1959

Imprimatur: + Joannes Kyne Epus. Miden. die 2 Maii 1959

CONTENTS: PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

HOLINESS OF LIFE

MEANS TO HOLINESS

PIETY AND PRAYER

SACRIFICE

CHARITY

ZEAL

DIGNITY AND PROPRIETY

PREACHING

SOCIAL APOSTOLATE